Why in the news?

The editorial argues that with rising inequality, technological displacement, precarious gig work and climate shocks, India should re-examine its welfare architecture and consider placing a Universal Basic Income (UBI) — a regular, unconditional cash transfer to every citizen — at the core of social protection. The piece frames UBI as a pragmatic tool to provide basic economic security, rebuild citizen-state trust, support unpaid care work and smooth transitions caused by automation and climate stress.

Context

- As India’s economic disparity widens and technological progress outpaces policy adaptation, multiple structural challenges—automation-driven job losses, insecure gig work, and climate-induced displacement—have converged.

- In this environment, the idea of a Universal Basic Income (UBI), once viewed as an idealistic concept, has gained renewed policy significance.

- UBI represents more than a fiscal transfer; it seeks to restore dignity, economic stability, and a sense of equal citizenship amid rapid social and economic change.

- Analysing the UBI debate in India thus requires examining its economic, moral, administrative, and political dimensions, positioning it as a foundation for a new welfare compact suited to the 21st century.

Economic Inequality and the Moral Imperative

- India’s growing income and wealth inequality forms the ethical core of the argument for UBI.

- Although official data highlight around 4% GDP growth in 2023–24, the benefits remain heavily concentrated—the richest 1% own about 40% of national wealth, while the top 10% control 77%.

- As economist Joseph Stiglitz argues, GDP figures cannot capture equality, sustainability, or well-being. India’s 126th position in the 2023 World Happiness Report illustrates the mismatch between economic expansion and social welfare.

- Within this context, UBI serves as both a moral and economic stabiliser.

It provides a minimum income floor that enhances autonomy, reduces vulnerability, and restores human dignity. - By simplifying welfare delivery through unconditional cash transfers, UBI bypasses leakages and exclusion errors common in targeted schemes.

- It also recognises unpaid household and care work, largely performed by women, as a vital yet undervalued contribution to the economy.

Universality as Administrative and Philosophical Strength

- The concept of universality gives UBI its most distinctive advantage.

Unlike traditional welfare schemes that depend on eligibility tests and bureaucratic discretion, a universal model links entitlement to citizenship rather than poverty status. This approach eliminates stigma, minimises corruption, and simplifies administration. - Philosophically, universality turns basic income into a rights-based social guarantee rather than a discretionary handout.

- It embodies the principles of a modern welfare state—streamlined, unconditional, and resilient against automation shocks or climate crises.

By rooting welfare in citizenship, UBI reshapes the meaning of inclusion, ensuring that every individual is an equal stakeholder in national prosperity.

Economic Rationale and Empirical Evidence

- Empirical experience reinforces UBI’s feasibility. The SEWA–UNICEF pilot in Madhya Pradesh (2011–13) demonstrated that direct, unconditional transfers improved nutrition, school attendance, and productivity.

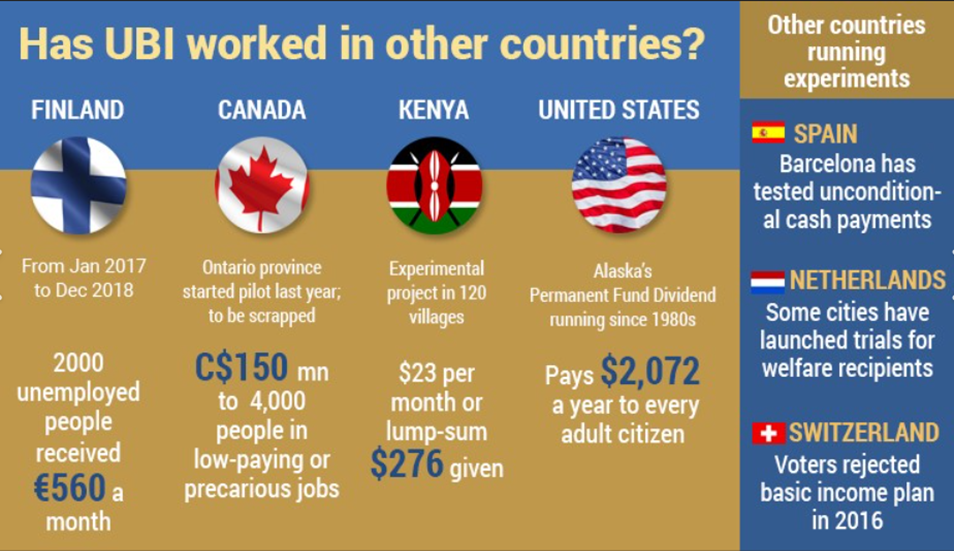

- Similar experiments in Finland, Kenya, and Iran reported gains in mental health, food security, and labour participation—refuting fears that basic income discourages work.

- With estimates suggesting that automation could displace up to 800 million jobs globally by 2030, India’s informal and low-skilled workforce remains particularly vulnerable.

- A basic income acts as a transition buffer, enabling reskilling, mobility, and adaptation.

Hence, UBI should be seen not as a welfare expenditure but as a long-term investment in social resilience and human capital formation.

Major Universal Basic Income (UBI) Experiments Worldwide

United States:

- Alaska Permanent Fund: Since 1982, every resident of Alaska has received an annual dividend of about USD 1,000–2,000 from the state’s oil and gas revenues — a long-standing form of partial UBI.

- Freedom Dividend: Proposed by Andrew Yang during the 2020 U.S. presidential elections, this plan aimed to provide every adult citizen with USD 1,000 monthly to mitigate the impact of automation on employment.

Norway: Although Norway doesn’t have a formal UBI system, its extensive welfare framework ensures universal access to healthcare, education, and social security. However, benefits are conditional on fulfilling certain obligations like job-seeking and tax compliance.

Finland: In 2016, Finland piloted a two-year basic income program involving 2,000 unemployed individuals who received USD 640 monthly. The study found that participants experienced improved well-being, mental health, and autonomy while being freed from constant unemployment verification.

Brazil:

- Bolsa Família (2004): A conditional cash transfer program that provides approximately 20% of the minimum wage to the poorest 25% of Brazilians, ensuring access to food, education, and healthcare.

- Santo Antônio do Pinhal: Implements one of the earliest municipal-level UBI models, distributing part of local tax revenues to long-term residents.

- Quatinga Velho (2008): A privately funded UBI experiment that has significantly improved nutrition, education, and overall living standards, particularly among children.

Reconstructing the Citizen–State Relationship

- Beyond its economic rationale, UBI redefines the moral and political relationship between citizens and the state. It challenges India’s patronage-driven welfare politics, in which short-term freebies are exchanged for electoral support.

By separating income security from political favour, UBI empowers citizens to evaluate governance based on performance in education, healthcare, justice, and sustainability. - This marks a shift from a consumerist democracy—where benefits are transactional—to a citizenship-based democracy founded on rights and accountability.

- When economic security is guaranteed, citizens can demand good governance instead of depending on subsidies.

- UBI thus emerges as an instrument of democratic renewal, replacing charity and populism with a rights-oriented social contract.

Funding and Implementation Challenges

- The principal constraint lies in UBI’s fiscal and operational feasibility.

Even a modest annual payment of about ₹7,620 per person—approximately the poverty line—could cost around 5% of India’s GDP.

Meeting this expense would require comprehensive tax reforms, subsidy rationalisation, or a gradual, phased rollout. - However, the core question has shifted from “Can India afford UBI?” to “Can India afford the consequences of mass insecurity?” A pragmatic approach could begin with targeted pilots for vulnerable groups—women, elderly persons, and people with disabilities.

- India’s expanding digital infrastructure—Aadhaar, Jan Dhan, and Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT)—offers a reliable base for large-scale delivery, though digital access and literacy gaps in remote areas must be addressed to ensure universality.

Moreover, UBI should complement, not replace, existing welfare mechanisms such as PDS and MGNREGA, at least during the early phase of implementation.

Conclusion

- UBI is not merely a fiscal instrument—it represents a vision of equitable and dignified citizenship for a rapidly changing India.

- By embedding autonomy, security, and justice within welfare policy, it offers a blueprint for a renewed social contract that is both economically resilient and democratically inclusive.

- A carefully designed, phased, and fiscally balanced UBI could anchor India’s welfare architecture in universality and rights rather than charity and discretion.

- Ultimately, the real question is no longer whether India can afford a Universal Basic Income, but rather whether it can afford the social and democratic costs of leaving millions excluded from basic economic security.

Source: Redraw welfare architecture, place a UBI in the centre – The Hindu