Context: The Supreme Court of India recently issued notice on a petition arising from a case in which a woman stands accused of ‘penetrative sexual assault’ against a minor boy.

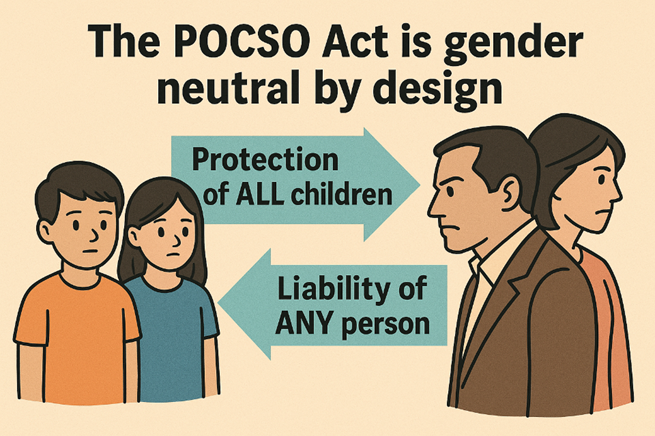

Introduction: The POCSO Act, enacted in 2012, provides a special legal framework to protect children (i.e., persons under 18) from sexual offences, sexual harassment and pornography involving children. A key feature in contemporary jurisprudence is its gender-neutrality—it protects all children and makes all persons (irrespective of gender) liable under the law.

What does “gender-neutral” mean in this context?

“Gender-neutral” here has two dimensions:

- Victim side: Protection is extended to all children, boys and girls alike.

- Offender side: Liability is on any person (male or female) committing or facilitating sexual offences against children.

Thus the Act does not conceptualise only a male perpetrator and a female child victim; rather, it adopts a broader, inclusive formulation.

Legal/Statutory basis for gender-neutrality

Several statutory and interpretative features support this:

- The Act defines “child” as a person below 18 years of age, without reference to gender.

- Section 3 (definitions of offences) uses the word “person” in its opening clause (e.g., “whoever commits…” / “a person …”) which is gender-neutral

- Though certain provisions may use the pronoun “he”, the general interpretive rule under Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC) Section 8 is that “he” includes “she”. The Act by reading Section 2(2) along with IPC Section 8 enables that interpretation. Judicial pronouncements: For example, the Karnataka High Court held on 18 Aug 2025 that the POCSO Act is gender-neutral, and envisages prosecution of a woman offender against a boy victim.

- Commentaries explicitly state that the Act was drafted with the intention of offering “a thorough, gender-neutral strategy to protect children from sexual exploitation and abuse, regardless of their gender.”

- The 2019 Amendment to POCSO strengthened the gender-neutral understanding.

Why is this important / what are the implications?

- Inclusive protection: By recognising that boys too can be victims of sexual abuse (and women too can be perpetrators), the law widens the protective net and removes the assumption that only girls are victims and only men are offenders. The Karnataka High Court observed a Government-study that 54.4% of children reporting sexual assault were boys.

- Breaking gender stereotypes: Historically many sexual offences laws (especially rape laws) were predicated on male-perpetrator/female-victim binary. A gender-neutral law challenges that binary, signalling modern jurisprudence evolving beyond stereotypes.

- Accountability of all offenders: If women or non-traditional configurations (e.g., female teacher with male child) underpin the offence, the law allows prosecution and does not exclude them. The Karnataka judgment refused to accept the argument that a woman cannot commit penetrative sexual assault under POCSO.

- Victim’s access to justice: Male victims or victims of female perpetrators may otherwise find exclusion or reluctance owing to societal prejudice; gender-neutral framing helps mitigate that barrier.

Key interpretative issues (for UPSC answer)

- Textual vs purposive interpretation: The text may sometimes use gendered pronouns (“he”) but the purposive reading (objects & reasons, legislative intent) coupled with interpretive rules (IPC Section 8) yields a gender-neutral application. The Karnataka High Court emphasised this.

- Penetrative assault definitions: For example Section 3(a) of POCSO uses “he penetrates his penis…” but immediately expands to include “or makes the child do so with him or any other person”. Thus the law covers various acts, not strictly penile-vaginal between male-adult and female-child. The court held that limiting it to male perpetrator would be illogical.

- Delay in reporting / potency / stereotypical defence: The court in the Karnataka case rejected arguments that a woman cannot commit rape because men are the active participants, or because a child could not have a physiological reaction. The court observed that such stereotypical assumptions are archaic and not aligned with modern jurisprudence.

- Implementation & awareness issues: Although the Act is gender-neutral, in practice underreporting (especially of boy victims) and societal stigma remain as challenges. Some commentary notes that the mere statutory neutrality doesn’t ensure equitable implementation

Critiques / Challenges

- Some judgments, for example the earlier controversial Bombay High Court “skin-to-skin” contact interpretation, showed that implementation and interpretation can undermine the protective purpose

- Gender-neutrality is essential, yet societal attitudes (e.g., male victims, female perpetrators) often lag behind; thus the effectiveness of the law depends on training of police, judiciary, awareness among the public.

- Resources, infrastructure (special courts, child-friendly procedures), and sensitisation are still uneven across India, which affects realisation of the statute’s promise.