- Dark Adaptation: The physiological process by which the human eye increases its sensitivity to light when transitioning from a high-illumination environment (bright sunlight) to a low-illumination environment (dark room).

- The Latency Period: The temporary visual impairment experienced during this transition is caused by the time lag in the eye’s mechanical and chemical adjustments.

How does the Eye Mechanically Adjust? (The Pupillary Reflex)

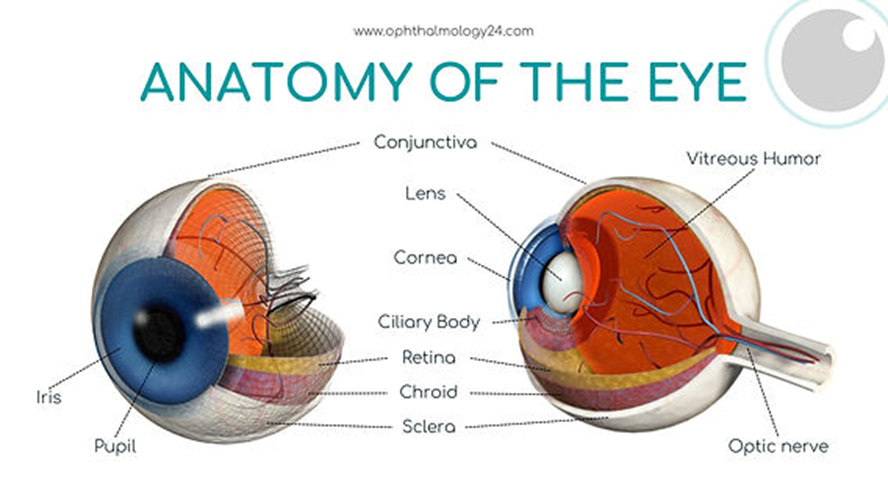

- Role of the Pupil: The pupil functions as a variable aperture, regulating the quantum of light entering the eye.

- In High Illumination: The pupil constricts (shrinks) to minimize light entry and protect the retina from photic damage.

- In Low Illumination: The pupil dilates (widens) to maximize light capture.

- The Constraint: When moving into darkness, the pupil is initially constricted. It requires time to dilate fully, contributing to temporary blindness.

How does the Eye Chemically Adjust? (The Rhodopsin Cycle)

The primary driver of dark adaptation occurs at the molecular level within the Retina.

- Photoreceptors: The retina contains two distinct types of light-sensitive cells:

- Cones: Active in bright light (Photopic vision); responsible for color perception and high visual acuity.

- Rods: Active in dim light (Scotopic vision); responsible for contrast and motion detection.

- The Rhodopsin Mechanism:

- Rod cells contain a photosensitive pigment called Rhodopsin (or Visual Purple).

- Photobleaching: Exposure to bright light causes Rhodopsin to decompose (break down) rapidly, rendering rod cells inactive.

- Regeneration: In darkness, Rhodopsin must normally resynthesize (regenerate) to restore light sensitivity. This regeneration is a slow biochemical process, causing the delay in vision recovery.

- vitamin A (Retinol) is a critical precursor for the synthesis of Rhodopsin. Deficiency leads to ‘Night Blindness’ (Nyctalopia).