After reading of the article you can solve this UPSC Model Question

“Freedom of speech under Article 19(1)(a) is not absolute but foundational to Indian democracy.” Examine the scope of this right and analyse how reasonable restrictions under A-19(2) have been interpreted by the judiciary. (GS 2 – Polity)

Context- The proceedings of the Supreme Court of India, in Ranveer Allahbadia vs Union of India and other cases have raised the worry that the potential risks of endangering speech could emerge from the Court itself.

Basic about A-19(1)

Article 19(1)(a) of the Indian Constitution guarantees freedom of speech and expression to all citizens, forming the bedrock of democratic governance by enabling free exchange of ideas, dissent and accountability.

Broad Scope and Significance of Article 19(1)(a)

The Supreme Court, through several landmark judgments, has given an expansive interpretation to this right, encompassing various implicit facets crucial for a functioning democracy:

- Freedom of the Press/Media:

Judgement- Romesh Thappar v. State of Madras (1950)

Significance– Essential for the free circulation of ideas and opinions; a powerful check on government.

- Right to Know/Access Information:

Judgement- State of U.P. v. Raj Narain (1975).

Significance- Citizens have a right to know every public act of their government; basis for the Right to Information (RTI).

- Right to Silence/Not to Speak:

Judgement- Bijoe Emmanuel v. State of Kerala (1986)

Significance- Freedom of expression includes the right to remain silent or express dissent through non-speech.

- Right to Fly the National Flag:

Judgenent- Union of India v. Naveen Jindal (2004)

Significance- Expressing patriotism is a form of expression under Article 19(1)(a).

- Right to Internet Access:

Judgement- Anuradha Bhasin v. Union of India (2020)

Significance- Expressing patriotism is a form of expression under Article 19(1)(a).

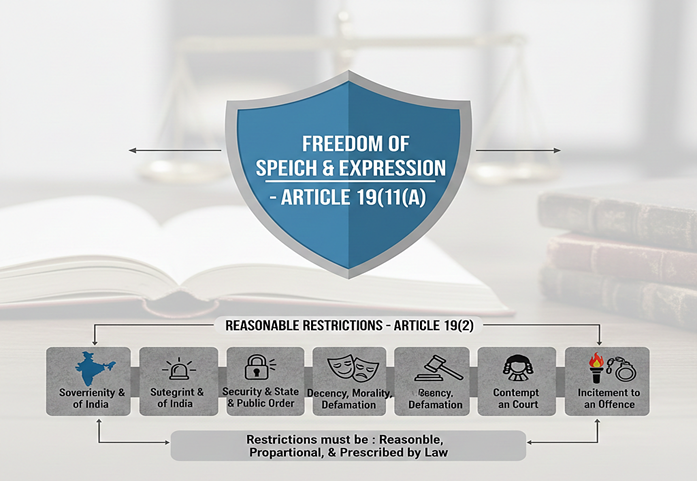

Grounds and Judicial Interpretation of Restrictions (Article 19(2))

Article 19(2) explicitly provides the State with the power to impose “reasonable restrictions” on the freedom of speech and expression on eight specific grounds, which have been judicially interpreted:

- Sovereignty and Integrity of India: This ground was added by the 16th Constitutional Amendment Act of 1963

- Key Interpretation/Rationale– To empower the State to curb expressions that challenge the territorial or constitutional integrity of the nation, primarily aimed at combating separatist or secessionist tendencies.

- Security of the State: This restriction is narrowly interpreted by the Judiciary. As established in the Romesh Thappar Case,

- Key Interpretation/Rationale– It refers only to aggravated forms of public disorder, such as acts threatening the national structure (e.g., rebellion or waging war), and not to minor, ordinary breaches of law and order.

- Friendly relations with foreign states: Introduced by the 1st Amendment Act of 1951, Key Interpretation/Rationale– this ground allows the government to restrict speech that is hostile, malicious, or defamatory towards foreign nations with whom India maintains friendly diplomatic relations, thereby protecting India’s international standing.

- Public Order: The courts distinguish this ground from ‘law and order’ and ‘security of the state.’ As seen in the Superintendent, Central Prison v. Ram Manohar Lohia case, Key Interpretation/Rationale- ‘public order’ concerns disturbances that are grave enough to affect the community or public at large, disrupting the general peace and tranquility of society.

- Decency or Morality: This ground relates to expressions that are considered offensive to the prevailing public standards of propriety and morality, often applied in the context of obscenity laws (such as Sections 292-294 of the Indian Penal Code) to protect public standards and ethics.

- Contempt of Court: This restriction is essential to ensure that the judicial process functions impartially, without being prejudiced, scandalized, or obstructed by public comments, thus maintaining the dignity and authority of the courts and the administration of justice.

- Defamation: This provision protects the fundamental right to reputation of individuals, which the Supreme Court has recognized as an integral part of the right to life under Article 21. Defamation can lead to both civil (damages) and criminal (punishment) proceedings.

- Incitement to an offence: Also added by the 1st Amendment Act of 1951, this ground restricts speech that directly, not remotely, encourages or provokes the commission of a cognizable offence, ensuring that freedom of expression does not become a license for criminal instigation.

Issues and Challenges Related to Article 19(1)

1. Vague and Overbroad Restrictions

The grounds for restriction under Article 19(2) are often criticized for their vagueness, allowing for potential misuse:

- Public Order: Despite judicial attempts (e.g., Ram Manohar Lohia Case) to establish a “proximate nexus” between the speech and the disorder, this ground is frequently invoked by the state for general policing actions or to suppress non-violent dissent (e.g., internet shutdowns, restrictions on protests).

- Decency or Morality: This ground is highly subjective, often leading to the arbitrary censorship of artistic expression, literature, and films based on the subjective “hurt sentiments” of a specific group, rather than on universal standards of public morals.

- National Security/Sovereignty: This is often cited in cases involving media bans (e.g., the MediaOne ban controversy) or the use of stringent laws like the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act – UAPA or the repealed Sedition Law (Section 124A, IPC), which have historically been criticized for stifling political dissent and journalistic watchdog functions.

2. The Digital Age Dilemma

The proliferation of online platforms has introduced new complexities:

- Hate Speech vs. Free Speech: India lacks a clear, comprehensive legal framework to definitively define and address online hate speech. The current reliance on various provisions of the IPC (e.g., Section 153A, 295A) often results in a “chilling effect” on genuine speech due to arbitrary arrests and FIRs.

- Misinformation and Fake News: The massive scale and speed of misinformation circulation threaten public order and communal harmony, yet regulating content platforms raises serious questions about digital censorship and the overreach of government agencies.

- Intermediary Liability: The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 (IT Rules, 2021) impose responsibilities on digital platforms, which critics argue forces them to become state censors, potentially violating user freedom of expression.

3. Protection of Expressive Conduct

The Supreme Court has struggled to articulate a clear, principled test to determine when expressive conduct (like protests, demonstrations, or artistic actions) should be protected under Article 19(1)(a). The lack of a uniform principle leads to ad-hoc judicial decisions.

4. Rise of Horizontal Harms

Recent judicial debates have focused on the “horizontal dimension” of free speech: the idea that one citizen’s speech can violate the fundamental rights (like the Right to Dignity under Article 21) of another citizen (especially marginalized groups), moving beyond the traditional “vertical” relationship between the citizen and the State.

Way forward:

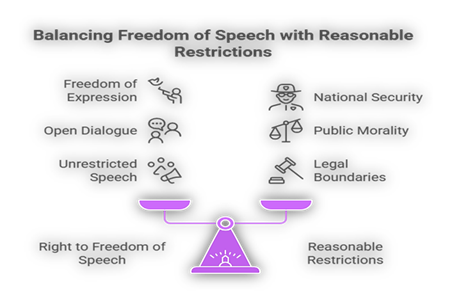

The Test of Reasonableness and Proportionality

The most crucial aspect is the judicial review of the restriction’s reasonableness.

- Test of Reasonableness: The restriction must be related to the grounds specified in Article 19(2), and the government must demonstrate a reasonable connection between the restriction imposed and the objective sought to be achieved.

- Doctrine of Proportionality: As laid down in Modern Dental College v. State of M.P. (2016), the restriction must be proportional. It means the extent of restriction must not be excessive or disproportionate to the evil it seeks to remedy. The least restrictive alternative should be chosen.

Conclusion

Freedom of speech under Article 19(1)(a) is essential for democracy, but its strength lies in a carefully balanced framework where individual liberty coexists with collective security and constitutional morality.