After Reading This Article You Can Solve This UPSC PYQ Question:

Analyse the role of local bodies in providing good governance at local level and bring out the pros and cons merging the rural local bodies with the urban local bodies.2024 (150 word, GS-2 Polity)

Context:

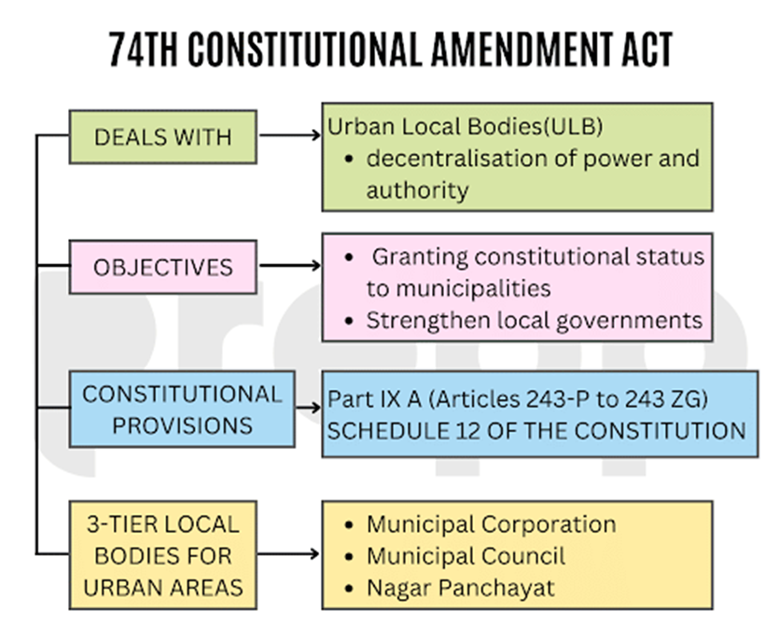

Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) are institutions of local self-government in urban areas, constitutionally recognized under the Constitution (Seventy-fourth Amendment) Act, 1992. This amendment inserted Part IX-A (Articles 243P–243ZG) and the 12th Schedule, which lists 18 functional subjects such as urban planning, water supply, sanitation, slum improvement, and public health.

Types of Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) in India:

In India, Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) are classified based on the size, population, and revenue of the settlement. Under the 74th Constitutional Amendment Act, there are three primary types, along with specialized administrative bodies.

1. The Three Constitutional Tiers

- Municipal Corporation (Nagar Nigam): Established for large metropolitan cities (e.g., Delhi, Mumbai, Bangalore). They deal directly with the State government and have more functional autonomy.

- Municipality (Nagar Palika): Established for medium-sized towns or smaller cities. They are divided into wards and governed by a municipal council.

- Nagar Panchayat: A body for transitional areas—places currently transforming from a rural (village) to an urban center.

2. Specialized Urban Bodies

| Type | Purpose | Key Feature |

| Notified Area Committee | For fast-developing towns or those not meeting municipality criteria. | Entirely nominated by the State Govt; no elections. |

| Town Area Committee | For small towns with limited civic functions (lighting, drainage). | Semi-autonomous; functions like a giant village panchayat. |

| Cantonment Board | For areas where military personnel and civilians live together. | Under the administrative control of the Ministry of Defence. |

| Township | Established by large Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs). | Provides civic amenities to employees (e.g., Steel City townships). |

| Port Trust | Managed by a board to protect and manage port areas. | Handles both civic and commercial port interests. |

| Special Purpose Agency | Created for specific functions (e.g., Delhi Development Authority). | Focuses on a single task like “housing” or “water supply” across city lines. |

Governance Structure of Urban Local Bodies (ULBs):

Regardless of the type, most ULBs share a common internal structure:

- The Council: The deliberative wing consisting of elected Ward Councillors.

- The Mayor/Chairperson: The titular head (elected or nominated depending on the state).

- The Commissioner: An IAS officer or state cadre official who acts as the Executive Head to implement decisions.

Financial System of Urban Local Bodies (ULBs):

Sources of Revenue

- Own Tax Revenue- Property Tax (the mainstay), Profession Tax, Advertisement Tax. Post-GST, ULBs lost significant autonomy as Octroi and Entry Tax were subsumed.

- Own Non-Tax Revenue- User charges (water, sanitation), building license fees, rent from municipal properties, and fines/penalties.

- Fiscal Transfers Devolution: Based on State Finance Commission (SFC) and Central Finance Commission (CFC) recommendations.

- Grants: Scheme-specific funds (AMRUT, SBM 2.0).

- Market-Linked and Innovative Financing- Municipal Bonds, Loans from HUDCO/Banks, and Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs).

The proposed Urban Challenge Fund seeks to:

- Make urban projects “market-linked”

- Require cities to raise 50% funding through bonds/loans

- Provide 25% central support

Structural Fiscal Problems of Financial System of ULBs:

India’s municipal revenue is around 1% of GDP, much lower than global standards (5–8% in developed countries).

- Vertical & Horizontal Imbalance: A massive gap exists between the vast constitutional responsibilities of ULBs and their narrow tax base (less than 1% of GDP), alongside a sharp disparity between “Mega-Cities” and dependent Tier-II/III towns.

- Loss of Productive Taxes: Before GST, ULBs collected Octroi and Entry Tax, which were buoyant and grew with the economy.

- Dependency: Post-GST, these were subsumed, making ULBs dependent on “Compensation” from the State/Centre, which is often delayed, leading to the “long delays” mentioned in the article regarding the National Health Mission and other schemes.

- Functional Overlap: States have devolved functions (from the 12th Schedule) but not the funds or functionaries to manage them.

- Committed Liabilities: A lion’s share of ULB budgets (often 60%-80%) goes toward “Revenue Expenditure” (salaries and pensions), leaving negligible funds for “Capital Expenditure” (new infrastructure).

- Poor Accounting: Many ULBs still don’t maintain audited annual accounts or use double-entry bookkeeping. This makes it impossible for them to access the “Urban Challenge Fund” or issue Municipal Bonds.

Government Initiatives for ULBs:

- Urban Challenge Fund (UCF): A ₹1 lakh crore flagship aimed at making cities “bankable.” The Centre provides 25% funding only if ULBs raise 50% via market instruments (Bonds, PPPs) across growth, redevelopment, and sanitation verticals.

- Credit Repayment Guarantee: A ₹5,000 crore corpus providing a 70% guarantee (up to ₹7 crore) to help Tier-II, Tier-III, and Himalayan/NE cities access market loans for the first time.

- AMRUT 2.0 (Water Security): Targets 100% water supply in 4,378 towns and sewage management in 500 cities. It promotes the circular economy through “Jal Hi AMRIT” (wastewater reuse) and “Pey Jal Survekshan.”

- SBM-Urban 2.0 (Garbage Free): Focuses on 100% waste segregation, remediation of all “legacy dumpsites” (landfills), and ensuring zero discharge of untreated used water into the environment.

- PM e-Bus Sewa: A green mobility drive to deploy 10,000 electric buses across 169 cities using a PPP model, including support for charging infrastructure and depot modernization.

- Digital & Reform Push: Extends Smart City missions for ICCC completion, uses TULIP for youth internships in ULBs, and mandates digital land records and property tax improvements for grant eligibility.

Way Forward:

- Empowering Fiscal Autonomy: States must transition from “controlling” to “facilitating” by devolving actual taxing powers and allowing ULBs to update property tax registers and circle rates without political interference.

- Administrative Capacity Building: Prioritize the adoption of double-entry accrual accounting and digital land records. Without transparent books, smaller cities cannot leverage the Credit Repayment Guarantee Scheme.

- Balancing “Bankability” with Service: While pursuing “monetizable assets,” the Centre must ensure Minimum Service Guarantees. Market-linked finance should supplement, not replace, funding for non-profit social sectors like slum formalization.

- Strengthening Master Plans: City planning must move from “violations and regularizations” to strict enforcement. A “Master Plan” should be a legally binding document that ensures long-term sustainability rather than short-term profit.

- Institutionalizing Performance Grants: Future funding (like the UCF) should be linked to measurable outcomes—such as the percentage of waste segregated or water audited—rather than just the ability to borrow.

- Protecting Vulnerable Populations: As cities move toward cost-recovery models (user fees), robust social safety nets and protections for renters and low-income households must be integrated into the urban reform agenda.

Conclusion

The future of Indian cities lies in transforming ULBs from “grant-seekers” into fiscally autonomous hubs. By harmonizing market discipline with social equity, cities can leverage digital governance and transparent accounting to build resilient, bankable, and inclusive urban ecosystems for a billion citizens.