Why in the News?

The critical issue of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) has been brought into sharp focus by recent global surveillance reports, highlighting the alarming rate at which common infections are becoming untreatable. This phenomenon, often referred to as a “slow-moving pandemic,” poses a profound threat to public health and the very foundations of modern healthcare systems worldwide.

Why the Concern?

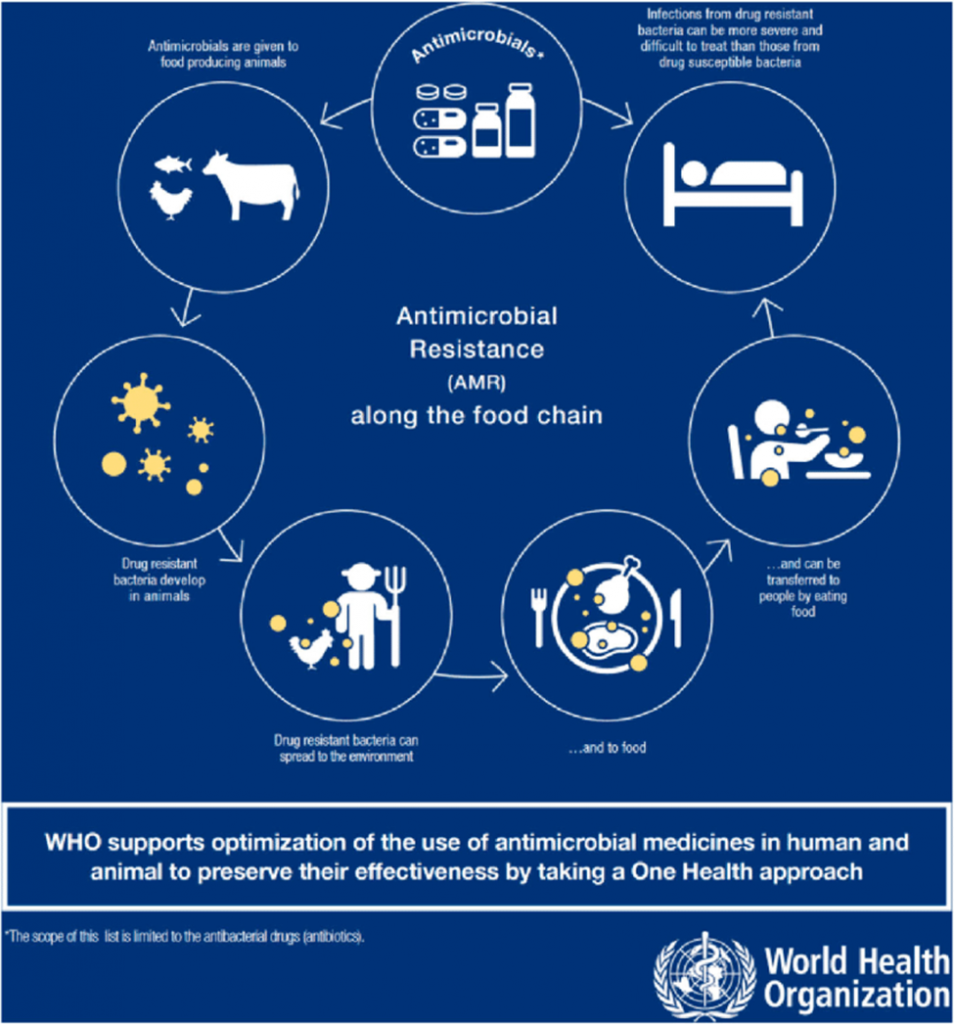

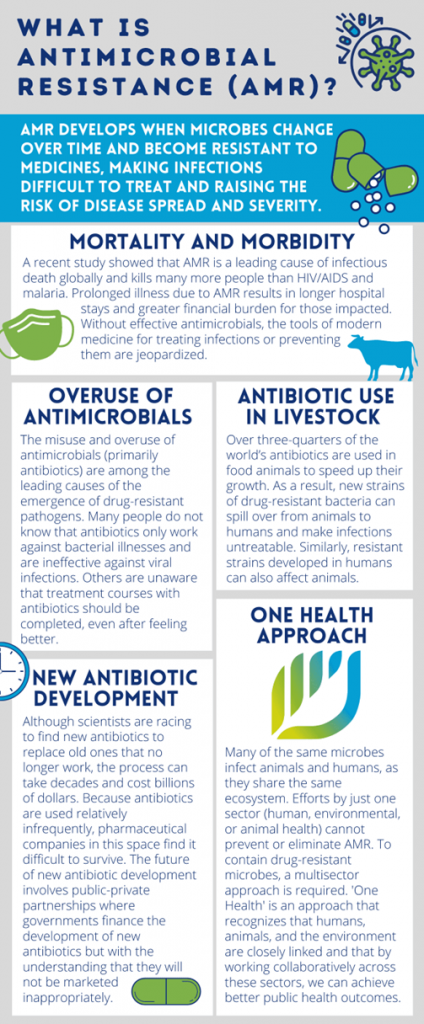

AMR occurs when microorganisms, such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites, develop resistance to the drugs designed to kill them. This makes antibiotics and other antimicrobial medications ineffective, leading to prolonged illness, increased mortality, and higher healthcare costs. Recent data from international bodies often shows high resistance levels for crucial pathogens, signaling a severe challenge, particularly in densely populated regions.

Understanding the Drivers of Resistance

The proliferation of antimicrobial resistance is a complex, multi-sectoral challenge driven by several factors, which are often interrelated.

1. Misuse in Human Health

- Irrational Prescribing: Healthcare professionals often prescribe broad-spectrum antibiotics without first confirming the cause of infection (empirical therapy), leading to unnecessary exposure for bacteria.

- Patient Behaviour: Self-medication and the failure to complete the full course of antibiotics, often due to improved symptoms, allows the most resilient bacteria to survive and multiply.

- Accessibility: Easy over-the-counter access to antibiotics in many regions bypasses essential medical guidance.

2. Excessive Use in Agriculture and Livestock

- Growth Promoters: Antibiotics are routinely used in livestock and poultry, not just for treating disease, but to promote faster growth and prevent illness in crowded conditions. This creates a vast reservoir of resistant bacteria that can enter the human food chain and the environment.

- Example: The use of antibiotics like Colistin (a ‘last resort’ drug for human infections) as a growth promoter in animal feed directly compromises its effectiveness for critical human use, although many countries have now banned this practice.

3. Environmental Contamination

- Pharmaceutical Effluent: Untreated waste discharge from drug manufacturing units often contains high concentrations of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). These ‘hotspots’ in rivers and soil allow microbes to rapidly evolve resistance.

- Poor Sanitation: Inadequate sewage treatment and hospital waste management systems enable resistant bacteria from human and animal waste to spread widely into water sources and the soil.

Key Challenges in Combating AMR

Despite national and international action plans, several systemic obstacles hinder effective control of AMR.

- Weak Regulatory Enforcement: While regulations exist, such as restrictions on prescription-only antibiotics, enforcement often remains weak, allowing for continued unregulated sale and misuse.

- Lack of Rapid Diagnostics: The scarcity of affordable, point-of-care diagnostic tests means doctors must often guess the pathogen and prescribe broad-spectrum drugs. This makes it difficult to implement antibiotic stewardship effectively.

- The Research and Development Vacuum: The pipeline for developing new antibiotics is critically low. This is primarily an economic problem, as new antibiotics are used sparingly to prevent resistance, making them less profitable than drugs for chronic diseases.

- Poor Inter-sectoral Coordination: Effective intervention requires a collaborative ‘One Health’ approach, integrating human health, animal health, and environmental policy. Coordination across different government ministries (Health, Environment, Agriculture) remains a significant challenge.

The Way Forward: A Comprehensive Strategy

A robust, coordinated, and well-funded strategy is essential to turn the tide against AMR.

1. Strengthening Stewardship and Diagnostics

- Example: Implementation of mandatory Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs (ASPs) in all hospitals. These programs involve multidisciplinary teams (doctors, nurses, pharmacists) who review and guide the rational use of antibiotics. For instance, an ASP can mandate that certain critical antibiotics are only released after approval by an infectious disease specialist.

- Investment in Diagnostics: Subsidizing and promoting the use of cheap, rapid diagnostic tests at all levels of healthcare, from rural clinics to major hospitals, to enable targeted treatment.

2. Robust Environmental and Agricultural Policy

- Example: Implementing a ‘zero-tolerance’ policy for pharmaceutical effluent discharge containing high levels of APIs. This requires mandatory treatment facilities and stringent penalties for non-compliance, ensuring that manufacturing sectors do not contribute to environmental resistance.

- Phasing Out Non-Therapeutic Use: Completely banning the use of medically important antibiotics for growth promotion in animals and strengthening veterinary supervision.

3. Financial Incentives for Innovation

- Example: Governments can explore innovative financing models like the ‘subscription model’ (often called the ‘Netflix model’ for antibiotics), where pharmaceutical companies are paid a fixed annual fee for access to a new antibiotic, rather than basing payment on the volume of sales. This removes the financial disincentive for companies to develop and sparingly use new drugs.

4. Enhancing Public Awareness

- Community Education: Launching sustained, targeted, and culturally relevant public campaigns to educate the populace that antibiotics do not work on viruses (like the common cold or flu) and the importance of completing prescribed courses.

Conclusion

Antimicrobial Resistance is a slow-burn crisis that, if unchecked, could lead the world back to a pre-antibiotic era where routine infections and minor injuries are fatal. Addressing this global threat requires decisive political commitment, significant investment in surveillance and innovation, and above all, the seamless implementation of the ‘One Health’ framework. The responsibility lies not just with doctors and scientists, but with policymakers, industry, farmers, and every citizen, making it a truly collective fight for the future of global health.

UPSC CSE PYQ

| Year | Question |

| 2014 | Can overuse and misuse of antibiotics lead to antibiotic resistance? What are its implications and how can it be controlled? |

| 2017 | Examine the public health challenges posed by the growing incidence of antimicrobial resistance in India. Suggest measures to address the issue. |

| 2020 | What do you understand by the term ‘One Health’? Discuss how it can help in tackling future pandemics. |

| 2021 | What are the challenges related to antibiotic misuse in livestock and poultry? Suggest measures. |

| 2022 | ‘Cooperative Federalism is essential in managing public health crises.’ Discuss with examples. |

| 2023 | Discuss the challenges of pharmaceutical pollution and its impact on ecology and human health. |

| 2023 | The One Health approach has become central to global health governance. Discuss. |

| 2024 | Examine India’s progress in implementing the National Action Plan on AMR. |