Why in the News?

The article implicitly or explicitly draws attention to the persistent issues facing the Anganwadi ecosystem:

- Low Remuneration and Recognition: AWWs and AWHs are classified as honorary workers or volunteers, not government employees, leading to meagre, non-minimum-wage honorariums (often between ₹5,000 and ₹10,000 per month) and frequent delays in payments. This creates financial insecurity and demotivation.

- Overburdened with Multitude of Tasks: Anganwadi workers are tasked with a diverse and heavy workload, including:

- Health & Nutrition: Supplementary nutrition distribution (Hot Cooked Meals, Take-Home Rations).

- Early Childhood Education (ECCE): Pre-school education and play activities.

- Community Mobilization: Counseling parents, conducting health check-ups, and promoting healthy behaviors.

- Administrative Duties: Record-keeping, growth monitoring, and conducting surveys (e.g., Census, election, and recent COVID-19 related duties).

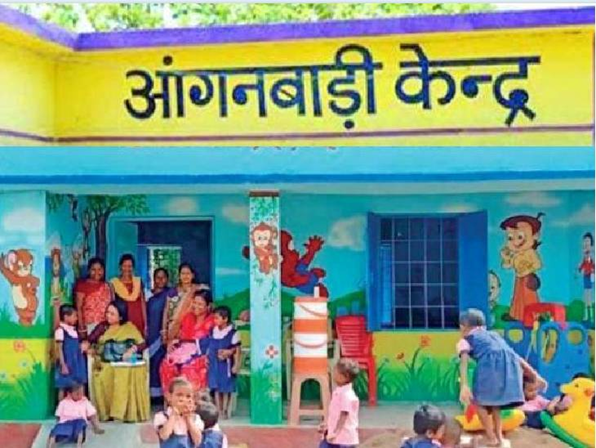

- Lack of Basic Infrastructure: Many Anganwadi Centres (AWCs) lack basic amenities like their own buildings, functional toilets, drinking water, and electricity, severely hampering the quality of service delivery.

Key Analysis: The Anganwadi System – Pillars of the Care Economy

The Anganwadi system is the foundation of India’s social infrastructure, especially in rural and disadvantaged areas. Analyzing its role is central to the topic of Social Justice and Human Development.

1. Role in Human Development and Social Justice

- Addressing the Vicious Cycle of Malnutrition: AWCs are the primary mechanism for delivering Supplementary Nutrition to pregnant women, lactating mothers, and children under six. They are essential in breaking the vicious cycle of gender inequality, poverty, and malnutrition.

- Enabling Women’s Labour Force Participation (LFP): By providing childcare and early education, AWCs act as an essential public good. The availability of quality, affordable childcare services directly reduces the burden of unpaid care work on women, enabling them to re-enter or remain in the formal or informal labour force.

- Foundation for ECCE: AWCs are mandated by the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 to provide Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) for the 3-6 age group, preparing children for formal schooling and ensuring SDG 4.2 compliance (quality early childhood development).

2. Undervaluation of the Care Economy

The issues faced by AWWs reflect the systemic undervaluation of the Care Economy—the sum of all paid and unpaid activities that provide care and support.

- Gendered Burden: Care work is disproportionately shouldered by women in India. By keeping AWWs as low-paid ‘honorary’ workers, the government perpetuates the notion that care is an unpaid, voluntary activity rather than a professional economic service, leading to gender inequality in wages and social protection.

- Lack of Decent Work: AWWs and AWHs, despite their vital function, struggle to access basic rights and entitlements that workers in the formal sector enjoy, such as fixed minimum wages, provident funds, and retirement benefits. This is a clear case of “informalization” of essential public service delivery.

3. Operational Gaps in ICDS

- Infrastructure Deficit: Lack of adequate, pucca buildings and basic amenities not only affects the quality of meals and education but also makes the centres unattractive to beneficiaries.

- Training and Technology Gap: Limited training, especially in the use of smartphones/tablets for real-time monitoring (ICT-RTM under POSHAN Abhiyan), hinders effective data collection and prevents optimal monitoring of growth among malnourished children.

- Limited Hours and Age Coverage: AWC services are often limited to a few hours a day and may not cater to children under three, which is inconvenient for working mothers and fails to align with the NEP 2020 mandate for the 0-6 age group.

- The path forward requires adopting the ILO’s 5R Framework—Recognition, Reduction, Redistribution, Rewarding, and Representation.

Challenges to the AWC System

- Status Quo vs. Minimum Wage: The classification of AWWs as ‘honorary’ workers prevents the application of minimum wage laws and social security benefits, despite their full-time work.

- Implementation Gaps: Schemes like the National Crèche Scheme have suffered from diminished government funding and limited implementation, leaving large coverage gaps, especially for informal women workers.

- Governance Overload: Over-reliance on AWCs for non-core administrative tasks (surveys, election duties) degrades their primary focus on ECCE and nutrition.

Way Forward: Institutionalizing and Professionalizing Care Work

- Professional Status and Compensation (Rewarding):

- Action: Transition AWWs and AWHs from ‘honorary’ workers to recognized public service functionaries or part-time government employees.

- Example: Ensure their monthly honorarium is linked to the National Minimum Wage or a corresponding State minimum wage for skilled labor, with provisions for pension and provident fund.

- Strengthening Infrastructure and Resources:

- Action: Expeditiously complete the construction of dedicated, well-equipped Anganwadi Centres (AWCs) with basic amenities (water, sanitation, electricity).

- Example: Ensure continuous supply of medical and educational materials, and promote a play-based learning strategy as envisioned by the NEP 2020.

- Skill and Capacity Building (Recognition):

- Action: Provide comprehensive and refresher training to AWWs in ECCE, health, and technological literacy for effective use of monitoring apps.

- Example: Create a clear career progression pathway (e.g., from Helper to Worker to Supervisor) to boost morale and professional recognition.

- Integration of Services (Reduction and Redistribution):

- Action: Extend the functional hours of AWCs and include provisions for children under three years of age to maximize utility for working mothers.

- Example: Converge AWCs with other schemes like the National Creche Scheme to establish childcare centres near industrial or labor clusters.

Source: Recognise the critical role of the childcare worker – The Hindu

UPSC CSE PYQ

| Year | Question |

| 2022 | Distinguish between ‘care economy’ and ‘monetized economy’. How can care economy be brought into monetized economy through women empowerment? |

| 2021 | Can the vicious cycle of gender inequality, poverty and malnutrition be broken through microfinancing of women SHGs? Explain with examples. |

| 2020 | In order to enhance the prospects of social development, sound and adequate health care policies are needed particularly in the fields of geriatric and maternal health care. Discuss. |

| 2016 | Professor Amartya Sen has advocated important reforms in the realms of primary education and primary health care. Examine the main provisions of the National Child Policy and throw light on the status of its implementation. |