Introduction: The Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of Electoral Rolls is an exercise undertaken by the Election Commission of India (ECI), primarily under the constitutional power granted by Article 324 and the statutory mandate of Section 21(3) of the Representation of the People Act, 1950 (RP Act).

The stated goal of the SIR, as per the ECI, is to clean up long-standing inaccuracies in the voter list, which may include:

- Duplicate entries (voters registered in multiple places).

- Deceased voters whose names were not removed.

- Migrated voters (permanently shifted).

- Inclusion of ineligible persons (e.g., non-citizens).

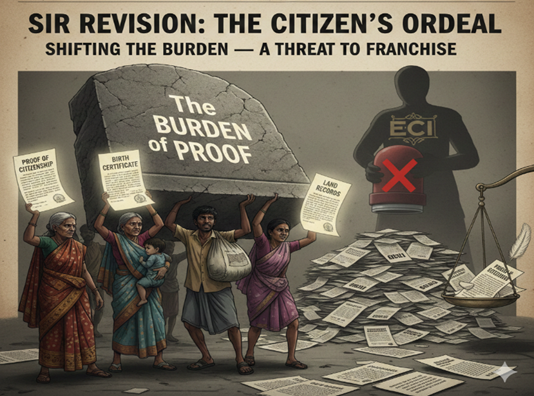

The Burden of Proof Inversion:

The central issue highlighted by petitioners is that the SIR methodology reverses the traditional, inclusive principle of universal adult franchise.

1. Traditional Principle (Inclusionary)

The established principle dictates that once a person’s name is on the electoral roll, there is a presumption of validity. The onus to prove ineligibility for deletion lies squarely with the State/ECI. This is executed through a statutory process involving Form 7 (Objection to inclusion), mandatory notice to the elector, and a quasi-judicial hearing by the Electoral Registration Officer (ERO).

2. The SIR Inversion (Exclusionary Concern)

In the SIR, the ECI introduced a mandatory Enumeration Form (EF) for all existing voters, particularly for those whose details could not be matched/linked with the last SIR’s data.

- The Shift: The act of requiring every elector to re-prove their eligibility through a new form and document matching process shifts the burden of proof from the ECI (to prove ineligibility) to the elector (to prove eligibility/citizenship).

- Vulnerability: This is deemed highly problematic for vulnerable sections (e.g., illiterate citizens, daily wage migrants, and women who lack old, specific documents like parent’s records) who may be unable to comply with the procedural requirements, leading to de facto disenfranchisement.

ECI Guidelines and Judicial Perspective:

The ECI, in its defense before the Supreme Court, has stressed its constitutional mandate and the necessity of the SIR exercise, but the judicial process has forced refinements concerning the burden of proof.

| Aspect | ECI Guidelines/Arguments | Judicial Concern |

| Legal Basis | ECI cites Article 324 (broad supervisory powers) and Section 21(3) of RP Act (power to order a special revision) to justify the pan-India exercise. | Petitioners argue the power under Section 21(3) is limited to a constituency or part of it, not an en masse exercise, and that Article 324 cannot “supplant” the statutory process. |

| BLO’s Role & Burden | ECI guidelines state that Booth Level Officers (BLOs) must make at least three visits to collect the filled-up Enumeration Forms (EFs). EROs must issue a notice and hear cases for electors whose names could not be linked/matched before deletion. | Specialist argue that tasking a BLO (often a school teacher) with a verification process that effectively determines citizenship (by demanding complex documents) is ultra vires and places an unreasonable burden on the voter. |

| Use of Documents | The ECI initially had a restrictive list of documents. The Supreme Court had to intervene to ensure that widely accepted documents like Aadhaar, Voter ID, and Ration Cards are considered to ensure an inclusive process, though it clarified Aadhaar is not proof of citizenship. | Petitioners argue that demanding documents beyond the scope of the RP Act and the Registration of Electors Rules (like parent’s legacy records for certain birth years) is an illegal imposition of the citizenship burden. |

Conclusion: The Conflict of Objectives

The discourse on the SIR is a classic tension between two vital democratic objectives:

- Purity of the Roll: The ECI’s objective to maintain an accurate electoral roll (one person, one vote) to prevent electoral fraud.

- Inclusivity of Franchise: The constitutional objective of ensuring that no eligible citizen is left out (universal adult franchise).

The method of shifting the burden of proof to the elector—thereby treating every registered voter as a potential ‘presumptive guest’—endangers the principle of inclusivity and risks widespread, unfair disenfranchisement of India’s poor and marginalised citizens. The argument is that the ECI must use its extensive institutional power to proactively verify and delete ineligibles, not rely on procedural default (non-submission of the form) to exclude citizens.