Why in the News?

The underlying theme in the news (often concerning mining projects like those in Chhattisgarh’s coal-rich areas or Odisha’s bauxite hills) is the alleged legal “hoodwinking” or bypassing of the mandatory provisions designed to protect Adivasi rights. Specifically:

- Undermining the Gram Sabha’s Veto Power: State governments and project proponents are often accused of facilitating forest diversion for non-forest purposes (like mining) without securing the Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) of the Gram Sabha, a mandatory requirement under both FRA and PESA.

- Conflict with New Rules: The Forest (Conservation) Rules, 2022, are seen by critics, including the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes (NCST), as potentially violating the FRA by allowing forest clearance to be granted before the process of recognition and vesting of forest rights is completed, thereby turning the Gram Sabha’s consent into a post-facto formality.

- Poor Implementation of FRA: Despite being a landmark social justice legislation, the FRA’s implementation is plagued by low claims recognition rates, recognition of less land than claimed (as seen in Chhattisgarh), and bureaucratic resistance, which leaves Adivasi communities vulnerable to displacement.

Constitutional and Legal Provisions: The Protection Framework

The rights of Adivasis are protected by a robust, multi-layered legal framework.

1. Constitutional Safeguards

| Provision | Mandate | Relevance to Adivasis |

| Fifth Schedule | Governs the administration and control of Scheduled Areas in 10 states (including Chhattisgarh and Odisha). | The Tribes Advisory Council (TAC) advises the Governor, and the Governor can modify Central/State laws in their application to Scheduled Areas. |

| Article 244 | Provisions for the administration of Scheduled and Tribal Areas. | Underpins the principle of self-governance and protection of tribal culture and land. |

| Article 46 | Directive Principle of State Policy mandates that the State shall promote the educational and economic interests of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes and protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation. | Forms the moral and policy basis for special legislation like FRA and PESA. |

2. Statutory Pillars of Self-Governance

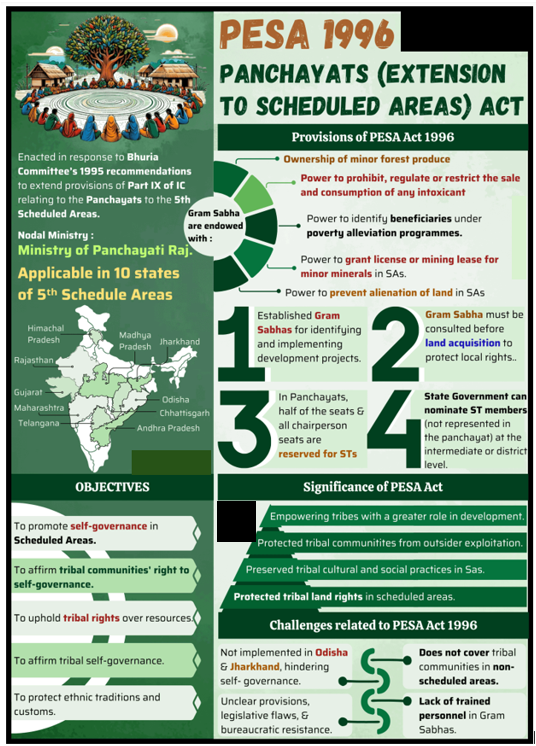

- Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act (PESA), 1996:

- Self-Governance: Recognizes the Gram Sabha as the central authority for self-governance in Scheduled Areas.

- Mandatory Consultation: The state must consult the Gram Sabha for land acquisition, project planning, and exploitation of mineral resources.

- Safeguard: Empowers the Gram Sabha to safeguard and preserve the traditions, customs, cultural identity, community resources, and the customary mode of dispute resolution.

- Forest Rights Act (FRA), 2006:

- Recognition of Rights: Vests two main types of rights: Individual Forest Rights (IFR) for habitation and cultivation (max. 4 hectares) and Community Forest Rights (CFR) over common property resources, grazing, and Minor Forest Produce (MFP).

- Decision-Making Power: Section 4(5) states that no member of a forest dwelling Scheduled Tribe or Other Traditional Forest Dweller shall be evicted or removed until the process of recognition and verification of their rights is complete.

- Consent Clause: Mandates the prior informed consent of the Gram Sabha for the diversion of forest land for non-forest purposes.

Critical Analysis: The Challenge of Implementation

Despite strong legal provisions, the implementation often fails due to a combination of bureaucratic resistance, political will, and legislative conflicts.

1. Conflict of Laws: FCA vs. FRA

The core tension lies in the clash between the Forest Conservation Act (FCA), 1980, which prioritizes the Central Government’s approval for forest diversion, and the FRA, 2006, which prioritizes the Adivasi community’s consent through the Gram Sabha.

| Parameter | Forest Conservation Act (FCA), 1980 | Forest Rights Act (FRA), 2006 |

| Goal | Conservation: Centralizing the power to prevent large-scale diversion of forest land. | Social Justice: Recognizing historical injustice and vesting rights in forest dwellers. |

| Key Authority | Central Government / Forest Advisory Committee (FAC) | Gram Sabha (Village Assembly) |

| The Conflict | The Forest Conservation Rules, 2022, delink the requirement of Gram Sabha consent from the initial ‘in-principle’ forest clearance stage. This de facto compromises the Gram Sabha’s veto power, as it is extremely difficult to reverse a clearance once granted by the Centre. | The Act mandates that the recognition of rights and Gram Sabha’s consent must be completed before diversion, placing community rights on par with forest conservation goals. |

2. Administrative and Bureaucratic Hurdles

- Forest Department Resistance: The Forest Department, accustomed to its colonial-era control over forests, often acts as a gatekeeper, creating procedural hurdles and resisting the transfer of power and management to the Gram Sabhas.

- Dilution of Claims: Data shows a significant trend in many states, including Chhattisgarh, where the area of land recognized under IFR is substantially less than the area claimed by the Adivasis, rendering the titles economically non-viable.

- Lack of Awareness: The complex legal procedures and documentation requirements are often inaccessible to Adivasi communities, who lack necessary literacy, leading to high rejection rates or incomplete claims.

3. Judicial Precedents and Their Violation

The Supreme Court’s Niyamgiri Verdict (2013) provides a clear precedent:

- The Supreme Court ruled that the clearance for mining in the Niyamgiri hills of Odisha would be subject to the Gram Sabha of the Dongria Kondh community deciding the matter of their religious and cultural rights. This decision affirmed the supremacy of the Gram Sabha under the FRA and PESA in matters concerning their traditional habitat and sacred sites.

- The continued efforts by state governments to revive such projects by re-challenging Gram Sabha resolutions (as seen in the Niyamgiri case) or by bypassing the consent clause through new rules (FCR, 2022) represent a direct challenge to the spirit of self-determination affirmed by the Apex Court.

Conclusion and Way Forward

The issue of Adivasi land rights and resource control is fundamentally a matter of reconciliation between development, conservation, and social justice. For the legal framework to truly protect India’s Indigenous people and its forests:

- Restoration of Gram Sabha’s Veto: The Forest (Conservation) Rules, 2022, must be amended to restore the requirement that the recognition and vesting of forest rights and Gram Sabha consent must precede the Stage-I (in-principle) forest clearance.

- Strict Adherence to Niyamgiri Precedent: All state agencies and the Central Government must be held accountable for strict compliance with the letter and spirit of the Supreme Court’s mandate on FPIC in Scheduled Areas.

- Capacity Building: Resources must be dedicated to strengthen the Gram Sabhas and the Forest Rights Committees (FRCs) through training, technical support (like GIS mapping for claims), and legal assistance to ensure the process of rights recognition is expedited and accurate.

- Integrated Governance: There is a need for a unified approach where the Ministry of Tribal Affairs (which oversees FRA/PESA) has a formal and mandatory consultative role in the decisions of the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (which oversees FCA).

The effective implementation of the FRA and PESA is not merely a bureaucratic task; it is a constitutional imperative for granting dignity, autonomy, and socio-economic justice to India’s Adivasi population.

Source: The legal hoodwinking of Adivasis – The Hindu

UPSC CSE PYQ

| Year | Question |

| 2024 | Elaborate on the provisions of the Fifth Schedule of the Constitution of India and discuss the administrative problems associated with the development of tribal areas. |

| 2020 | What are the reasons for the introduction of the ‘Extension to Scheduled Areas’ Act, 1996 (PESA)? Critically evaluate its implication on the tribal population. |

| 2019 | The Central Government’s Civil Aviation Policy (CAP) 2016, proposes to develop small airports as ‘No-Frills Airports’. Discuss the challenges in the implementation of the policy. |

| 2018 | Assess the importance of the Gram Sabha as the central point of decentralized governance. Highlight the issues in its implementation. |

| 2016 | How does the Forest Rights Act, 2006 address the environmental concerns of the forest dwellers? |

| 2015 | What are the impediments in the attainment of the goal of ‘Community Forest Resource Management’? |

| 2013 | Besides the functional and financial autonomy, the issue of non-implementation of the provisions of PESA Act, 1996 needs to be addressed for the empowerment of the Gram Sabhas. Discuss. |