The globalisation of higher education has seen a surge in the establishment of international branch campuses (IBCs) — foreign universities opening full or partial campuses in host countries. In India, recent regulatory changes permit foreign universities to set up campuses, aligning with the “Global India” agenda.

Why the Push for IBCs in India

- India seeks to become a global education hub, tapping into its demographic dividend of 300 million+ higher-education aspirants. For instance, five foreign universities obtained Letters of Intent recently to open campuses in India.

- IBCs promise exportable education credentials, technology transfer, global faculty, international brand value and research collaboration.

- India benefits by creating world-class educational infrastructure domestically, reducing “brain-drain”, enhancing employability and integrating into global knowledge flows.

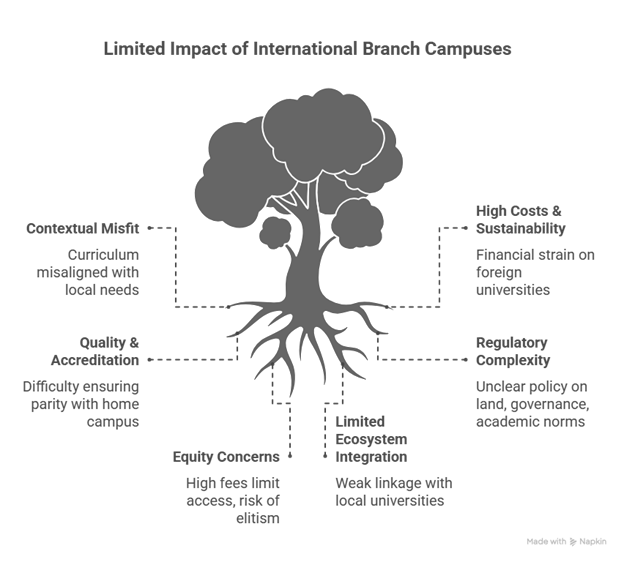

Limits and Constraints of International Branch Campuses

1. Contextual and Cultural Mis-fit

Foreign university curricula and pedagogy may not align fully with local socio-economic realities, regulatory frameworks, or employment ecosystems.

- Example: Global universities closing or scaling down overseas campuses due to unfavourable market context or regulatory misalignment.

- As a result, IBCs risk preparing students for jobs in foreign contexts rather than domestic ones, reducing relevance.

2. Cost and Sustainability Challenges

Setting up a full branch campus involves substantial land, infrastructure, faculty, accreditation and regulatory overheads. Many global institutions are financially stretched in their home countries, reducing appetite for risk.

- Example: UK universities opening campuses in India to tap student markets amid domestic financial woes.

- The long-term sustainability of IBCs in relatively less mature markets remains uncertain.

3. Quality and Accreditation Risks

Ensuring equivalence of teaching, research output, faculty quality, student experience between home and branch campuses is difficult. The global brand may overshadow actual quality.

- Example: Debate exists whether IBCs in host countries are mere “brand factories” rather than full research-oriented institutions.

- This raises concerns about maintaining national accreditation standards, learning outcomes and employability impact.

4. Regulatory and Governance Complexity

IBCs operate across jurisdictions — home country, host country and sometimes international accreditation bodies. This multi-layered regulation complicates governance.

- Example: India’s regulatory framework for foreign university campuses is evolving; full clarity on land, investment, governance models remains in flux.

- This uncertainty increases risks for host governments and universities alike.

5. Equity and Access Concerns

IBCs may serve mainly affluent segments able to pay high fees, thereby exacerbating educational inequality rather than broadening access.

- Example: High tuition of international campuses may make them inaccessible for many Indian students, limiting diversity and social impact.

- This limits their potential as instruments of inclusive development.

6. National Education Ecosystem Integration

If IBCs operate as enclaves without engaging local institutions, the spill-over benefits (faculty exchange, research linkages, curriculum localisation) may be limited.

- Example: Some branch campuses remain disconnected from the local ecosystem, thereby reducing benefits to indigenous institutions or regional innovation systems.

- This weakens the capacity for inter-institutional synergy.

Policy Implications & Way Forward

- Contextual Adaptation: IBCs must localise curricula, pedagogy and research agendas to Indian context and labour market.

- Sustainable Business Models: Fiscal incentives for IBCs should be balanced with viability assessments and safeguards for fee escalation.

- Quality Assurance: Strong regulatory oversight (via University Grants Commission, accreditation agencies) must ensure parity of standards between home and branch campuses.

- Equity Focus: Encouraging IBCs to provide scholarships, link with public institutions, and serve under-represented groups can enhance social inclusion.

- Ecosystem Integration: IBCs must partner with host-country institutions for joint research, faculty exchange, student mobility to ensure local capacity building.

- Regulatory Clarity: India must finalise transparent frameworks for land, investment, governance, home-country accreditation to reduce uncertainty.

- Monitoring & Evaluation: Host governments should monitor outcomes (graduate employability, research output, local spill-over) and adjust policy accordingly.

Conclusion: International Branch Campuses present a promising avenue for India’s higher-education internationalisation and global positioning. Yet, their benefits are not automatic — they are bounded by contextual fit, cost-viability, quality safeguards, regulatory complexity and equity considerations.