Why in the news?

The Supreme Court has begun examining whether statutory or regulatory restrictions that bar married couples with secondary infertility from using surrogacy (to have a second child) infringe on reproductive autonomy. The Court’s review follows petitions challenging provisions of India’s surrogacy laws that limit access and appear to treat primary and secondary infertility differently. The matter raises constitutional questions (right to privacy, personal liberty and reproductive choice), and has wide policy, ethical and social ramifications.

Context & significance

Surrogacy regulation balances reproductive rights, protection of surrogate mothers, prevention of commercial exploitation and child welfare. How the law treats secondary infertility—when a couple cannot conceive or carry subsequent pregnancies despite having a previously born child—tests the coherence of India’s regulatory approach and its commitment to reproductive autonomy and gender justice.

Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021

Definition and Nature of Surrogacy

Surrogacy refers to an arrangement where a woman agrees to conceive and deliver a child on behalf of another couple, and subsequently hands over the newborn to them after birth.

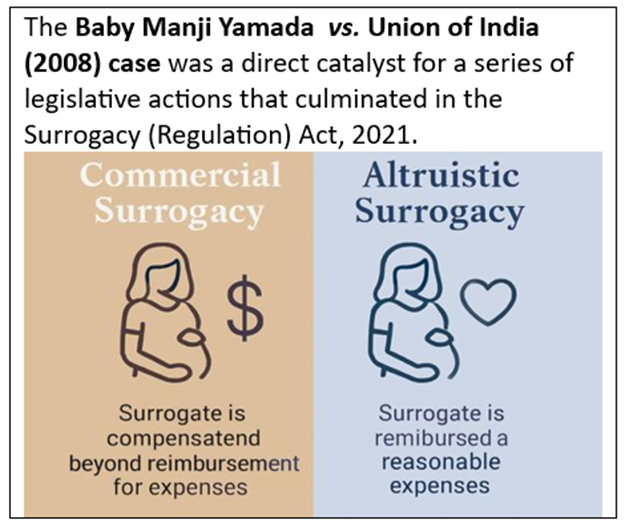

The 2021 Act permits only altruistic surrogacy, where no monetary compensation or commercial transaction is involved, apart from medical expenses and insurance coverage for the surrogate.

Eligibility Conditions for Intending Couples

- The intending couple must be legally married for at least five years.

- Age criteria: the wife should be between 25–50 years, and the husband between 26–55 years.

- They must not have any surviving child, whether biological, adopted, or through a previous surrogacy, except in cases where the existing child is mentally/physically challenged or has a life-threatening illness.

- Couples must obtain both eligibility and essentiality certificates from the designated authorities before opting for surrogacy.

Eligibility Conditions for the Surrogate Mother

- The surrogate must be a close relative of the intending couple.

- She should be married and have at least one biological child of her own.

- Age range: 25 to 35 years.

- A woman can act as a surrogate only once in her lifetime to prevent medical and emotional exploitation.

Regulatory and Oversight Mechanisms

- The Act provides for the establishment of National and State Surrogacy Boards to supervise and regulate the surrogacy process.

- Every surrogacy clinic must be registered and function in compliance with prescribed ethical and medical standards.

Offences and Penalties

- Commercial surrogacy, sale or purchase of embryos, and exploitation of surrogate mothers are criminal offences.

- Penalties include imprisonment up to 10 years and/or a fine of up to ₹10 lakh.

Legal Status and Rights of the Child

- A child born through surrogacy is deemed the biological child of the intending couple, with all corresponding rights.

- Termination of pregnancy during surrogacy can occur only with the surrogate’s written consent and in accordance with the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act, 1971.

Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Act, 2021

Scope and Registration

The ART Act governs all forms of assisted reproductive procedures, including IVF, sperm/egg donation, and embryo transfer, where gametes are handled outside the human body to facilitate conception.

All ART clinics and ART banks must obtain registration with the National Registry, valid for five years, to ensure transparency and accountability.

Eligibility and Restrictions for Donors

- Sperm donors must be men aged 21–55 years.

- Egg donors must be married women aged 23–35 years with at least one biological child aged three years or above.

- A woman can donate eggs only once, and a maximum of seven eggs may be retrieved per donation.

Prohibitions and Ethical Safeguards

- The Act strictly prohibits sex selection and any form of advertising ART services.

- The sperm of one donor can be used for only one intending couple to prevent genetic overlaps.

- Written informed consent and insurance coverage for all donors are mandatory prerequisites.

Legal Status of the Child and Oversight

- Children conceived through ART are legally the biological offspring of the intending couple, and donors have no parental rights or obligations.

- The National and State ART Boards oversee ethical practices, policy implementation, and compliance with standards.

Penal Provisions

- Offences such as sale of embryos, abandonment of children, or donor exploitation attract penalties between ₹5–10 lakh for the first violation, with imprisonment of 8–12 years for subsequent offences.

Critical analysis — legal & constitutional dimensions

- Right to reproductive autonomy and privacy

- Right to make decisions about family and reproduction flows from the right to privacy and personal liberty (Article 21). Restricting access for secondary infertility raises questions about whether the state can dictate family size or the means to have children.

- The Court must balance individual autonomy with the state’s interest in protecting surrogate mothers and preventing commodification.

- Proportionality and reasonableness of restrictions

- Any restriction on fundamental rights must be reasonable, proportionate, and have legitimate state aims. The government argues exploitation prevention and ethical safeguards — both legitimate — but the proportionality (is a blanket bar or exclusion necessary?) is contestable.

- Differential treatment between primary and secondary infertility may not pass strict scrutiny unless justified by evidence that it prevents specific harms.

- Gender and bodily integrity

- Surrogacy involves another woman’s body and labour. The state has a duty to prevent exploitation, ensure informed consent, and protect surrogate welfare (healthcare, insurance, counselling). Regulations must not unduly curtail reproductive choices in the name of protection.

- Best interests of the child & parentage issues

- Laws also aim to ensure clear parentage, citizenship, and the welfare of the child born by surrogacy. Any expansion of access must retain safeguards (parental responsibility, registration, abandonment prevention).

Social, ethical & policy implications

- Equity and social norms: Excluding couples with a living child may reflect moral judgments about family size and reinforce discriminatory norms; it can disproportionately affect infertile women and couples seeking family completion.

- Access & marginalisation: Restrictive eligibility could drive desperate couples towards unregulated, cross-border, or commercial arrangements, increasing risks of exploitation.

- Moral hazard vs reproductive justice: Policymakers fear misuse (e.g., sex-selection or surrogacy for non-medical reasons). But blanket exclusions risk infringing reproductive justice — the right to have children, to not have children, and to raise children in safe environments.

- Impact on surrogate mothers: Any liberalisation must be accompanied by robust protections: medical safety, living standards, informed consent, prohibition of coercion and trafficking.

Policy gaps & administrative issues

- Lack of clarity & evidence base: The law appears to differentiate primary vs secondary infertility but lacks transparent data-backed justification for differential treatment.

- Implementation capacity: Monitoring clinics, ensuring non-commercial conduct, and enforcing consent/compensation rules remain weak.

- Inter-legislative coordination: ART regulation, adoption law, medical ethics, criminal law (trafficking) and civil law (parentage) must be aligned.

- Cross-border surrogacy: Restrictive domestic law may push citizens to foreign surrogacy markets, raising jurisdictional, citizenship and child welfare issues.

Comparative treatment: primary vs secondary infertility

| Aspect | Primary Infertility | Secondary Infertility |

| Definition | Inability to conceive or carry a pregnancy to term in a couple who have never had a live birth. | Inability to conceive or carry a pregnancy to term after having previously given birth to a child. |

| Medical Causes | May arise from congenital or hormonal issues, ovulatory dysfunction, blocked fallopian tubes, low sperm count, etc. | Often due to acquired factors such as Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, infections, or lifestyle-related issues after the first childbirth. |

| Legal Treatment under Surrogacy Law (India) | Recognised under the Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021 as a legitimate ground for seeking surrogacy. | Currently excluded from surrogacy eligibility if the couple has a surviving biological, adopted, or surrogate child—except in cases of disability or life-threatening conditions. |

| Policy Rationale for Difference | Seen as a case of essential family formation for childless couples. | Considered less urgent by policymakers, assuming family is already “complete,” though this view is medically and ethically contested. |

| Social Implications | High social stigma due to complete childlessness; often emotional and social pressure on women. | Emotional distress and family pressure to have a second child; still stigmatized but often overlooked in public discourse. |

| Ethical and Rights Perspective | Denial of surrogacy would directly affect right to family and reproductive autonomy. | Restriction raises constitutional concerns of privacy, autonomy, and equality—argued as arbitrary and discriminatory. |

Way forward — policy recommendations

- Evidence-based eligibility review: Amend or reinterpret surrogacy rules to allow medically certified secondary infertility cases access, subject to safeguards — supported by medical evidence and legislative clarity.

- Rights-based framework: Recast surrogacy regulation to balance reproductive autonomy with surrogate protection (informed consent, counselling, health, insurance, minimum living standards).

- Proportionality test in legislation: Replace blunt exclusions with context-sensitive criteria (medical necessity, psychosocial evaluation) and time-limited exceptions.

- Strengthened oversight: Create a statutory regulatory authority (or empower existing boards) for ART and surrogacy clinics with inspection, licensing, grievance redressal and penalties for violations.

- Comprehensive welfare for surrogates: Mandate medical care, mental health support, assured compensation for loss of earnings, and enforce non-coercion provisions.

- Coordination across laws: Harmonise surrogacy law with adoption statutes, birth registration, nationality laws and anti-trafficking frameworks to prevent legal vacuums.

- Public awareness & counselling: Provide community education on surrogacy ethics, rights of all parties, and reduce stigma around infertility.

- Pilot and review: Introduce phased policy reform with pilot programmes, data collection, and periodic judicial/legislative review.

Conclusion

Regulating surrogacy requires a nuanced balance between the reproductive rights of intending parents and the protection of surrogate mothers and children. Blanket exclusions—such as denying access to those with secondary infertility—must be re-examined through constitutional principles of autonomy and proportionality, backed by medical evidence and robust safeguards to prevent exploitation.

Source: The second issue: On surrogacy for a second child – The Hindu

UPSC CSE PYQ

| Year | Question |

| 2018 | .Recently Lok Sabha passed the Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill 2016. Discuss the need, provisions and concerns with regard to the bill. |