After reading this article, you can solve the UPSC Mains PYQs given below

What are the impediments in disposing the huge quantities of discarded solid waste which are continuously being generated? How do we remove safely the toxic wastes that have been accumulating in our habitable environment? (GS 3, Subject: Environment, UPSC MAINS 2018)

Why in the News?

- Recently, the issue of waste management and urban pollution has been brought to focus following discussions at the 30th Conference of the Parties (COP30) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) held at Belem, Brazil.

- During the conference, waste was placed at the heart of the global climate agenda, and substantial funding was committed to the new global initiative “No Organic Waste, NOW”, aimed at reducing methane emissions.

- The concept of Circularity was identified as a crucial pathway to achieve inclusive growth, cleaner air, and healthier populations, aligning with India’s Mission LiFE (Lifestyle for Environment) that promotes deliberate utilisation over destructive consumption.

Background: Global Climate Context

- COP30 and Recognition of Waste as Climate Issue: At the 30th Conference of the Parties (COP30) to the UNFCCC, hosted at Belem, waste management was recognised as a critical climate variable influencing emissions and urban sustainability.

- Significant financial commitments were announced for the global initiative “No Organic Waste (NOW)”, which was designed to reduce methane emissions arising from unmanaged organic waste.

- Circularity was formally endorsed as a development pathway that enables inclusive growth, cleaner air, and healthier populations.

- Cities across the world were urged to accelerate circular economy initiatives, where waste streams are recognised and utilised as resources rather than discarded residues.

- India’s Contribution through Mission LiFE: Mission LiFE (Lifestyle for Environment), articulated by India at COP26, promoted the principle of deliberate utilisation instead of mindless and destructive consumption.

- Mission LiFE was firmly anchored in circular economy thinking, emphasising behavioural change as essential for environmental sustainability.

Urban India and Escalating Waste Crisis

- Urban Expansion and Environmental Stress: Expansion of cities and towns was described as an irreversible reality accompanying India’s economic and demographic growth.Urban development was framed as a clear choice between clean, liveable cities and waste-ridden, polluted urban spaces.Several studies were cited to indicate that Indian cities do not meet global standards in providing clean and healthy living environments.

- Pollution and Governance: The National Capital Region (NCR), along with several other Indian cities, was identified among the most polluted urban regions in the world.

- Governments, regulatory agencies, and even courts were stated to be actively intervening, yet tangible outcomes remained limited.

- Citizen grievance related to pollution and waste management was reported to be at its highest level.

- The Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) was acknowledged for eliminating open defecation, while its continuing objective was identified as making cities clean and garbage-free.

- Pollution and Governance: The National Capital Region (NCR), along with several other Indian cities, was identified among the most polluted urban regions in the world.

Scale of Urban Waste and Climate Implications

- Projected Waste Generation: Indian cities were estimated to generate 165 million tonnes of waste annually by 2030, contributing significantly to urban environmental stress.

- Urban waste was projected to emit more than 41 million tonnes of greenhouse gases, adding to India’s climate challenge.

- By 2050, with urban population expected to reach approximately 814 million, waste generation was projected to rise sharply to 436 million tonnes annually.

- Consequences of Delayed Intervention: Absence of early solutions was expected to result in grave emission levels, while simultaneously harming public health, economic productivity, and overall climate stability.

The objective of achieving Garbage Free Cities (GFC) by 2026 was described as an existential necessity rather than an issue of urban aesthetics.

Transitioning to a Circular Economy Model

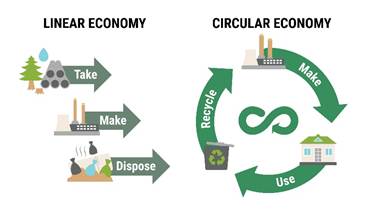

A transition from linear mode (take-make-dispose) to circular mode (minimize-recover-reuse) mode of waste management has been advocated for India, focusing on minimizing waste while recovering energy and other vital resources.

- SBM Urban 2.0: Under SBM Urban 2.0, approximately 1,100 cities and towns have been rated free of dumpsites, though complete garbage freedom requires all 5,000 cities and towns to adopt the circular economy model, treating waste as a valuable resource.

Municipal Waste Composition and Management Pathways

- Organic Waste and Energy Recovery:

- More than half of municipal waste generated in Indian cities was identified as organic in nature.

- Organic waste was stated to be manageable through household-level composting, community composting, and large bio-methanation plants.

- Complete combustion of organic waste was also noted to facilitate electricity generation.

- Dry Waste and Plastic Challenge:

- Over one-third of urban waste was categorised as dry waste, which is not fully recyclable.

- Plastic waste was identified as the most problematic component due to its harmful impact on ecosystems and human health.

- Effective dry waste management was stated to depend heavily on efficient segregation at household level.

- Material Recovery Facilities (MRFs) were recognised as critical infrastructure requiring continuous expansion to match growing waste volumes.

- Refuse Derived Fuel (RDF) from dry waste was identified as emerging energy source for cement and industrial sectors, although this segment remained under consolidation.

- Significant gaps were noted in entrepreneurship development and market linkages necessary for dry waste circularity.

- Wastewater and Water Security:

- As water and sanitation are State subjects, proactive steps are required to recycle wastewater for agriculture, horticulture, and industrial use.

- Water security is seen as having a causal link with faecal sludge management under missions like AMRUT and SBM.

- Construction and Demolition (C&D) Waste:

- Approximately 12 million tonnes of construction and demolition waste annually were generated in India.

- Unauthorised dumping of construction debris along roadsides and city lanes was described as common practice.

- C&D waste was identified as a major urban pollution source, arising largely from rapid and sometimes unplanned construction activity.

- Economic Potential: C&D waste can be recycled into cost-efficient raw materials, though current recycling capacity is insufficient.

- Regulatory Framework of (C&D) Waste:

- The Construction and Demolition Waste Management Rules, 2016 were designed to levy charges on bulk waste generators and define operational responsibilities.

- The Environment (Construction and Demolition) Waste Management Rules, 2025 were scheduled to come into effect from April 1, 2026.

Structural Hurdles and Bottlenecks in Circularity

The path to achieving a waste-to-resource transition is complex, involving a shift from the traditional “take-make-dispose” mindset to a systemic “loop” of resource recovery.

- Logistical Complexity and Multiplicity of Actors: The waste management ecosystem involves a fragmented chain consisting of households, informal waste pickers, urban local bodies (ULBs), and private contractors.

- Poor coordination between these actors often leads to a breakdown in the collection and distribution logistics, preventing waste from reaching processing units in a timely and organized manner.

- Persistent Source Segregation Challenges: Despite the mandates under SBM Urban 2.0, the smooth functioning of source segregation remains far from ideal.

- When wet (organic), dry (recyclable), and hazardous waste are mixed at the household level, the efficiency of downstream processing plants—such as bio-methanation and plastic recycling units—is severely compromised, leading to higher operational costs.

- Market Vulnerability and Financial Unfeasibility: Recycled products frequently face quality concerns and lack established market linkages, making it difficult for them to compete with cheaper, virgin raw materials.

- Without a robust demand-side policy or price-preference for “green” products, circularity projects struggle to achieve financial viability and long-term sustainability.

- Infrastructure and Monitoring Gaps: There is a significant shortfall in the technical infrastructure required for testing and monitoring the quality of processed waste.

- Many municipalities lack the equipment to ensure that recycled outputs meet industrial standards, and the current reach of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) remains limited, covering only a fraction of the total dry waste generated.

- Accountability and Traceability in C&D Waste: Construction and Demolition (C&D) waste management is hindered by the lack of identification and tracking of waste origin.

- Unlike municipal waste, C&D waste is often dumped clandestinely; its management is currently not integrated with building laws and construction permits, which prevents a clear chain of accountability for large-scale generators.

- Shortfall in Municipal Resource Capacity: Many Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) face severe resource shortfalls, ranging from a lack of technical expertise to inadequate funding for circularity projects.

- This prevents the scaling of material recovery facilities and bio-methanation plants, leaving smaller towns and cities unable to transition away from traditional dumpsites.

- Inter-Departmental and Regulatory Silos: Meaningful circularity is often obstructed by a lack of inter-departmental coordination between environment, urban development, and industrial departments.

- For instance, while the Ministry of Environment sets rules, the actual implementation depends on ULBs, and the market for the end-products depends on industrial policy, creating a governance gap.

- Rising Consumerism and Behavioral Barriers: In an increasingly consumerist society, the first two ‘Rs’ of the hierarchy—Reduce and Reuse—are becoming difficult propositions.

- As products and consumable items arrive in new incarnations daily, the “disposable culture” creates a psychological barrier to circularity, making “Recycling” the only viable pillar despite it being the most energy-intensive of the three.

Way Forward: Strategic Roadmap for a Circular Urban India

Achieving the Garbage Free Cities (GFC) 2026 goal requires a multi-dimensional approach that transcends mere waste collection to embrace holistic resource recovery.

- Strengthening Municipal Finance: Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) must resolve resource shortfalls by adopting self-sustaining models, such as graded user fees, Green Bonds, and Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) for infrastructure.

- Formalizing the Informal Sector: Integrating waste pickers and kabadiwalas into the formal municipal fold through Self-Help Groups (SHGs) ensures better source segregation and social dignity for the frontline workforce.

- Technological Integration in Recycling: Investing in automated Material Recovery Facilities (MRFs) and scaling up Refuse Derived Fuel (RDF) production will establish recycling as the strongest feasible pillar of circularity.

- Strict Regulatory Compliance for C&D Waste: Accountability must be enforced by integrating waste-origin tracking into building bylaws and construction permits, ensuring compliance with the 2025 Rules.

- Expansion of EPR Framework: The scope of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) needs to be expanded beyond plastics to include all categories of dry waste, supported by a digitized tracking system to prevent leakages.

- Decentralized Organic Waste Management: Given that over 50% of waste is organic, cities should prioritize decentralized bio-methanation and composting units to reduce transportation costs and methane emissions.

- Fostering Citizen Partnership: Participation should be incentivized by providing citizens with a clear sense of profit (e.g., deposit-refund schemes) and a collective purpose to counter rising consumerism.

- Regional and Inter-departmental Collaboration: Leveraging initiatives like the Cities Coalition for Circularity (C-3) and improving coordination between urban, environment, and industrial departments is vital for a holistic rejuvenation.

Conclusion

The transformation of urban India from a “waste-ridden” landscape to a “circular resource hub” is not merely an environmental target but a blueprint for sustainable economic growth. By aligning the Cities Coalition for Circularity (C-3) with domestic missions like SBM Urban 2.0 and AMRUT, India can create an inclusive system where every discarded item finds a renewed purpose. The success of this transition will ultimately define the resilience and health of an Aspirational India in the decades to come.