The fundamental reasons India continues to grapple with hazardous air quality, especially during winter in the Northern Plains, can be distilled into three key areas:

1. Fragmentation of Governance and Accountability

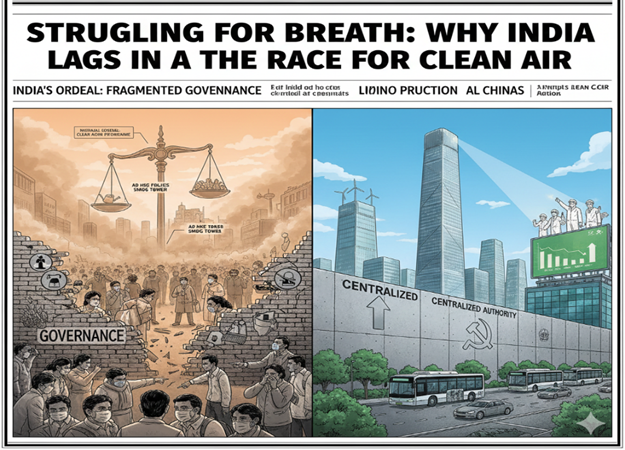

- Divided Authority: The problem of air pollution often circulates in a vast, shared airshed covering multiple states (like the Indo-Gangetic Plain). However, the authority to control emissions is severely fragmented. It is split between Central Ministries, State Departments, Municipal Bodies, and specialized regulators.

- Mixed Incentives: The lack of a single, accountable authority with overarching jurisdiction leads to a blame game. State governments often blame neighboring states (e.g., on stubble burning), the Centre blames states, and local bodies are often left without the necessary financial or technical resources.

- The Commission for Air Quality Management (CAQM): While the CAQM was created to address this fragmentation in the National Capital Region (NCR), editorials suggest its interventions are often limited and do not fundamentally change the behavior or incentives of the different state agencies involved.

2. Preference for Reactive ‘Quick Fixes’

- Emergency Measures over Continuous Action: India’s approach, particularly in Delhi-NCR, is characterized by knee-jerk reactions like the Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP). These measures (e.g., odd-even rules, construction bans) are triggered after pollution levels become hazardous.

- “High-Visibility” Solutions: The focus often shifts to visible, yet minimally effective, temporary solutions such as smog towers, cloud seeding, and water sprinkling. These actions demonstrate urgency but fail to tackle the root sources of pollution (transport, industry, power generation) continuously throughout the year.

3. Structural and Economic Challenges

- Inadequate Monitoring and Enforcement: Long-term analysis shows that existing regulation, monitoring, and enforcement across states and sectors remain insufficient. Many polluting industries operate with outdated technology or circumvent rules due to weak on-ground oversight.

- Household Emissions: India faces the unique challenge of widespread biomass burning in rural households for cooking and heating, contributing significantly to background pollution. While the LPG subsidy (Ujjwala Yojana) has helped, clean fuel remains unaffordable for many poor citizens.

Government Initiatives and Supreme Court Intervention

1. Government Response

The Government of India has launched the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP), aiming for a 20-30% reduction in Particulate Matter (PM) concentrations by 2024 (compared to 2017 levels) in 131 non-attainment cities.

- The Struggle: Critiques note that NCAP’s targets are non-binding, lack specific allocation of funds and responsibility, and suffer from the same fragmentation issues highlighted in the editorials, failing to integrate actions across transport, energy, and industry sectors effectively.

2. Supreme Court’s Role (SC Judgments)

The Indian judiciary, particularly the Supreme Court, has historically played a critical role through Public Interest Litigations (PILs), often filling the governance gap.

- Key Interventions: Past landmark orders led to the compulsory use of CNG in public transport in Delhi and the shift of highly polluting industries out of the city.

- Current Stance: However, recent Supreme Court observations reflect frustration with the lack of progress. In recent hearings (e.g., regarding the implementation of GRAP), the Court has criticised the Delhi government for its delayed response and the overall failure of authorities to implement past orders effectively.

- “No Magic Wand”: The bench has orally stated that the judiciary “does not have a magic wand” and emphasized the need to move away from “ceremonial listing” (hearing cases only during peak pollution) to a long-term, coordinated, and scientist-driven solution that is monitored year-round.

- Focus on Health: The Court’s directives to halt outdoor school activities during severe air quality days underscore the health emergency, labeling the exposure as “putting school children in a gas chamber.”

Comparative Achievement: Lessons from China

| Factor | China’s Strategy (Post-2013) | India’s Struggle |

| Political Will & Targets | Strong, top-down political commitment making clean air a core development priority. Linked air quality targets to cadre accountability (linking bureaucratic promotions to clean air results). | Short-term political incentives and a failure to sustain commitment. Accountability is weak and fragmented across federal and state levels. |

| Investment & Enforcement | Massive investment (e.g., $270 billion “war chest”) in pollution control, compulsory closure/upgrading of dirty coal-fired power plants and polluting heavy industries. | Insufficient and inconsistent funding for enforcement and technology upgrades. Widespread illegal operation and non-compliance. |

| Energy & Transport Shift | Aggressive shift from coal to natural gas/renewables (“coal-to-gas” initiative). Mass electrification of transport (e.g., fully electrifying bus fleets in Shenzhen). | Continued reliance on coal, slow pace of industrial greening, and lower penetration of electric mobility and clean public transport. |

| Governance Structure | Unitary state allowing swift, unified, and top-down implementation of policy without the jurisdictional overlap and political bargaining seen in India’s federal structure. | Fragmented governance where authority is diluted across multiple jurisdictions, slowing down coordinated action. |

Conclusion

India’s failure to clear its air is primarily a governance crisis, not a technical one. Experts suggest that India needs to transition from a reactive, crisis-management model (like GRAP) to a sustained, long-term national action plan (NCAP) that mandates clear, facility-level accountability, backs targets with heavy investment, and effectively addresses the political and administrative fragmentation across the vast northern airshed. The Chinese experience proves that significant improvement is possible with strong political will and sustained, comprehensive, science-based action.